Directed by: Park Kwang-hyun

Country of origin: South Korea (2005)

Starring: Shin Ha-kyun, Jeong Jae-yoeng, Kang Hye-jeong

I'm kicking things off with the Korean film that helped inspire this blog. Park Kwang-hyun's Welcome to Dongmakgol arrived to me during a time in which I was bored and completely uninspired. This film, fueled by its rich characters and its stoic cause, raised me out of that slump. Like most Korean films, Dongmakgol combines several genres (war, comedy, and drama), making for an incredibly unique cinematic experience. I approached it like any other film, yet partway through, I realized that Park's debut was slowly growing on me. At its end I was touched and, truthfully, near tears. Welcome to Dongmakgol is one of the most heartwarming and heartbreaking films I've ever seen. With its strikingly gorgeous cinematography and an ensemble of talented actors, Dongmakgol is a film that really sneaks up on you. It planted a seed inside of me, one fertilized by a dose of empathy, one exposed to a world of simple beauty. At sudden points in the film, it suddenly hits you, and Dongmakgol truly shines. Lets dive in.

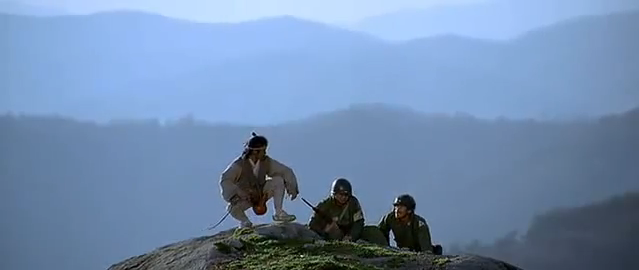

At its heart, Welcome to Dongmakgol is a satire of Korean conflicts and a critique on the Korean War. Through comedy and irony, Dongmakgol tells a story set in the darkest times of Korea's history. The nation's people are in the middle of a brutal cival war, one that left the country divided and changed forever. Park showcases the brutalities of war, showing the tragic points of view from both the Northern and Southern soldiers. At the film's beginning, the viewer is thrust immediately into the lives of the battered and wounded soldiers. The violence is sudden and massive, and an amount of empathy is undeniably established as the deaths of young Korean men are framed so strikingly on-screen. Upon close escape of death, and as the viewer has a chance to stop and breathe in relief, Park comes in and gets to work. With the fluttering of dozens of white butterflies, the soldiers enter the new world that will come to cleanse them of their impending stresses. A common motif throughout Dongmakgol, the white butterflies seem to float freely through the mountain skies like Japanese blossoms. They symbolize life, and the profound effect its simple presence has. This is the message of Welcome to Dongmakgol, that the warring people of Korea should simply abandon their violence and revert back to their heritage, life dedicated to beauty and simplicity.

The villagers of Dongmakgol live innocent lives. Their world exists only as far as their village and the forests surrounding it. They neither know nor care what lies beyond the mountains cradling them, and nobly so. Kind and gentle like children, they know nothing of the savage war that rages below them, and they welcome any and all visitors with the utmost amount of respect and hospitality, like their ancestors did before them. This simplicity is their way of life, and the central theme encompassing Welcome to Dongmakgol.

The villagers of Dongmakgol live innocent lives. Their world exists only as far as their village and the forests surrounding it. They neither know nor care what lies beyond the mountains cradling them, and nobly so. Kind and gentle like children, they know nothing of the savage war that rages below them, and they welcome any and all visitors with the utmost amount of respect and hospitality, like their ancestors did before them. This simplicity is their way of life, and the central theme encompassing Welcome to Dongmakgol.  When the soldiers wandered into the mountains, the gravity of their duties vanished, and to the villagers, any war High Comrade Lee and Second Lieutenant Pyo sought to rage against eachother was a simple argument. Firearms were sticks, and grenades were painted potatoes; to the villagers of Dongmakgol, these outsiders were just making a lot of noise about a simple feud. Words could resolve it, as far as they were concerned. And in this, Park Kwang-hyun and his intelligent screenplay make their point. The war and the soldier's grievances are made a mockery of in the presence of the villager's smart remarks and general cluelessness. In reality, the village is rounded up and held hostage at gunpoint by two factions of mortal enemies. But instead of being alarmed, the villagers appear to be more annoyed than anything. They have more pressing things to worry about than some pointless conflict between five strangers, like the wild boar thats been ravaging their food supply. They go about their hilarious, slapstick conversations and thus, the soldier's situation becomes nothing more than a silly standoff. Before they know it, the Northern and Southern soldiers were standing their, grenades and guns raised, for almost 24 hours straight, several of them struggling not to doze off while they remain standing. The situation is ridiculous and hilarious, and as the soldiers are drenched with rain and the villagers sit dry, giggling at the silly outsiders, the viewer begins to get it.

When the soldiers wandered into the mountains, the gravity of their duties vanished, and to the villagers, any war High Comrade Lee and Second Lieutenant Pyo sought to rage against eachother was a simple argument. Firearms were sticks, and grenades were painted potatoes; to the villagers of Dongmakgol, these outsiders were just making a lot of noise about a simple feud. Words could resolve it, as far as they were concerned. And in this, Park Kwang-hyun and his intelligent screenplay make their point. The war and the soldier's grievances are made a mockery of in the presence of the villager's smart remarks and general cluelessness. In reality, the village is rounded up and held hostage at gunpoint by two factions of mortal enemies. But instead of being alarmed, the villagers appear to be more annoyed than anything. They have more pressing things to worry about than some pointless conflict between five strangers, like the wild boar thats been ravaging their food supply. They go about their hilarious, slapstick conversations and thus, the soldier's situation becomes nothing more than a silly standoff. Before they know it, the Northern and Southern soldiers were standing their, grenades and guns raised, for almost 24 hours straight, several of them struggling not to doze off while they remain standing. The situation is ridiculous and hilarious, and as the soldiers are drenched with rain and the villagers sit dry, giggling at the silly outsiders, the viewer begins to get it.

THE POPCORN SCENE

Eventually, though, the hostility between the soldiers does culminate in a violent resolution, and creates what I believe to be the central scene of Welcome to Dongmakgol. Still standing and completely exhausted, young Northerner Taik-gi fumbles a live grenade and the soldiers run for safety, Lieutenant Pyo attempting to save the village by jumping to cover it. Although it at first appears to be a dud, Pyo tosses it blindly backwards in relief and the grenade lands, ironically enough, in the Dongmakgol food supply, exploding on contact. The corn and potatoes that were meant to last the villagers through the winter were all gone, but instead of being an atrocity, the explosion became a thing of beauty as popcorn floated down upon the village like soft flakes of snow. The villagers beam and dance, beholding this amazing gift that the mountain provided them. In result, one of the most significant and radiant scenes of the Korean New Wave cinema is born.

|

| Popcorn falls on Dongmakgol |

What makes this scene so successful is its clear symbolism and sudden shift in pace. Every physical element that upholds the popcorn scene is absolutely flawless, from the slow motion to the crisp depth to Hisaishi's angelic score. Upon exploding, it's almost as if the beautiful world surrounding it caused it to implode, and instead causing fear it caused joy. The air of simplicity that the village thrived on suffocated this man-made

What makes this scene so successful is its clear symbolism and sudden shift in pace. Every physical element that upholds the popcorn scene is absolutely flawless, from the slow motion to the crisp depth to Hisaishi's angelic score. Upon exploding, it's almost as if the beautiful world surrounding it caused it to implode, and instead causing fear it caused joy. The air of simplicity that the village thrived on suffocated this man-made of the film. It was almost as if the popcorn hypnotized them; their hatred was released, and they pondered skyward in awe and relief. Relief, so much, that the exasperated soldiers were finally lulled to sleep. The popcorn was like a lingering stun spore, the straw that broke the camel's back. The raging bears were coaxed into hibernation by an act of simple beauty, showcasing Dongmakgol's central message. The villagers acted accordingly,

innocent and oblivious as always, despite their massive loss of food. They grasped the moment of beauty at hand and treasured it. This was the scene where Dongmakgol truly began to move me. Master and legend of film score Joe Hisaishi composed music for the popcorn scene that absolutely gleamed like the sun. It showcased the emotion and the tone of the scene flawlessly. A true goosebump effect. It is in this scene that you begin to realize how intoxicating the atmosphere of Welcome to Dongmakgol is. You grow fond of the colorful characters and the pristine village that they reside in. And this emotional bond only grows from here, continuing to sneak up on you.

After their aggression is exhausted, things between the Northern and Southerners gradually improve, until respect and friendship is established, even between their zealous leaders Lee and Pyo. Any awkwardness is depleted as the men feast together on the boar they took down as a team. A simple human gesture of sharing food brought the warring people of North Korea, South Korea, and America

together. Park seems to dwell on this turning point in Welcome to Dongmakgol, perhaps commenting how the little things can make all the difference. The film itself indeed seems to live by that motto, taking time to explore the subtle beauties of the living and the inanimate alike. The soldiers spend the next few months helping the people of Dongmakgol replenish their food supply, and in doing so grow close with them and their way of life. Similarities between Dongmakgol and Edward Zwick's epic The Last Samurai arose in my mind. An outsider with a violent past, his presence obligated in a foreign place, proceeds to grow and adapt to the natural beauty and simplicity surrounding him.

Once the soldiers in Dongmakgol have to leave the village in order to save it from impending forces, sentimental moments between them and the villagers are heartbreaking. In the more serious moments of the film, Park did a fantastic job of making me feel pity for the victims. When the village chief is brutally beaten. When Pyo's flashback and past in finally fully revealed. The death of Yeo-il. Even the heartbreak of young Taik-gi. To me, the projected emotion was not a stretch, and I was moved in various instances throughout the film. In Dongmakgol, the village idiot, of sorts, Yeo-il is mainly used as a source of comic relief. But she actually becomes a symbol of the care-free lifestyle and the presence of love in the world of Dongmakgol. Her dances in the rain and popcorn.

|

| Yeo-il in the rain |

Welcome to Dongmakgol is a beautiful film with a valuable message. While hilarious in parts, director Park has also discovered a way to move his audiences with instances of heartbreaking drama. To me, the film was inspiring, and reminded me why I love East Asian cinema. It is a layered piece, and if you let it, it's stunning world will suck you in. In the end, after an apocalypse of sorts for the viewer has occurred, the white butterflies resurface from the snowy mountains and, in a very Miyazaki-esque way of doing it, tell us that life and hope still remain. The ending is not entirely resolved, and most viewers will naturally want to see Capt. Smith return to Dongmakgol, but what happens to the villagers and the survivors is never known. But it doesn't need to be. As with many of Korea's greatest films, Dongmakgol ends subtilely and satisfyingly, giving the viewer the closure they need yet leaving them with a taste for more. I'll say it once more, Welcome to Dongmakgol touched me; it warmed and broke my heart in all the right ways. It is quite the experience.

***** / *****

Having first seen this film a couple months back, I wasn't as enthusiastic about this film as you. I felt it borrowed a little too much from Hayao Miyazaki. Firstly, Joe Hisaishi's score is epic, but it's nearly identical to that in Princess Mononoke, as is the boar scene, which we see at the very beginning of Princess Mononoke. Then there's just the overall atmosphere of Dongmakgol (i.e., the village), which feels like it could've come from many of Hayao Miyazaki's films. In that respect, Welcome to Dongmakgol felt a bit too derivative, like a sort of live-action Miyazaki.

ReplyDeleteI also had a hard time not wincing during the performances of the Western actors in this film. A lot of Korean films are employing Western actors these days, including Address Unknown, Please Teach Me English, and The Host. In each case, they deliver unfailingly horrendous performances.

The way the five soldiers head out to protect the village is two soldiers short of Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai while, thematically, this film seemed to echo points made in Park Chan-wook's Joint Security Area. Soldiers from opposing sides become chums, which eventually culminates in tragedy. I would argue, however, that Joint Security Area, while admittedly lacking the comedic elements of Welcome to Dongmakgol, is by far the superior film.

The actor playing Smith was horrible! I completely agree in that respect. He was just a little too over the top in a few specific scenes throughout the film. But this can also be seen in a film like Kitano's "Brother". Films like "Brother" and "Dongmakgol" both rely heavily on the acts of American actors, and in each of the films there were times when I found myself wincing and wondering to myself why someone did what they just did. But then you have to take into consideration that films like those were directed by Asian directors, who appear to be greatly independent from Western influences. "Brother" was not a success in the USA, and Dongmakgol isn't a film that the public would respond particularly well to either. I think the reason acting like that seems to be a mistake to us is because the script or the humor or even just the culture of that respective country isnt translating well over to english. Perhaps in korea an over the top reaction like Smith's would seem normal, yet seem laughable to us.

ReplyDeleteRegarding its likeness to Miyazaki's work, and having seen a loved all of his works, I dont think Dongmakgol necessarily borrowed heavily from any of his films. I wouldnt at all be surprised if Park was influenced by Hayao (as so many are these days) and incorporated an ideal of his into Dongmakgol, but I don't see anything verging on sampling. The lighthearted tone to the village and the world, the butterfly motif, and of course the Hisaishi score seem to be very Miyazaki-esque, but not so much that it was unoriginal. On the contrary, I believe Dongmakgol to be very original. I think primarily the colorful, childlike world maybe provoke some thoughts of Miyazaki

JSA is one of the few big korean films I havent seen, but it's high, high up on my list.

Oh, and if you ever decide to take anything that I say into account, trust what I'd say about film scores. I've been listening to Hisaishi for fifteen years; his music has been a true inspiration to me. Anyway, forgive me when I say that Dongmakgol's score varied immensely from Mononoke's. I do agree that the music in the boar scene is very, very similar to "The Furies" in the score to Mononoke-hime, but other than that, Hisaishi's composition for Dongmakgol is actually one of the most unique he's ever done, relying more heavily on Asian strings and guitars and only employing his trademark piano and five cellos as background support. He reverted back to some of his roots from films like "A Scene at the Sea" with those otherworldly voices, but other than that his Dongmakgol score was pretty fresh. The score to Mononke-hime is one of my favorite, and it tends to rely much more on drawn out bombastic percussions and grander symphnoes. Phew... sorry I could talk about Hisaishi all day!

ReplyDeleteYou seem to know more about Hisaishi's work than I do. I'm mostly familiar with his work on Miyazaki's films and, if I had to pick one of his Miyazaki film scores that most resembles that heard in Welcome to Dongmakgol, I'd definitely say Princess Mononoke. On the other hand, it had been a long time since I last watched Princess Mononoke when I saw Welcome to Dongmakgol. Still, I didn't even know Hisaishi had done the score until I started watching the film and then it hit me like a brick.

ReplyDeleteI have to disagree with you on your hyothesis about the apparent poor acting by Westerners in Korean films. I suspect that it's as a result of having little access to the acting talents of Western countries (the U.S. in particular). Some of them seem to be no more than South Korea expatriates picked off the street. The English teacher in Please Teach Me English spoke fluent Korean, so I doubt they imported her from the U.K. for her role. It would be interesting, I think, to learn more about how these Westerners get their roles in Asian productions, including some Hong Kong and Mainland China martial arts flicks that more than frequently involve colonialist themes and feature fights with gargantuan Western boxers or some such.

Anyway, definitely see Joint Security Area (which also includes a bit of poor Western acting). That film requires some suspension of disbelief in that there's no way any soldier could simply cross a bridge and enter North Korea, but get past that and it's one of Korea's most moving films and, in my opinion, the best reconciliation-themed film.

You're probably exactly right about the Western actors haha. From what I've read, very little thought goes into the actual talent of the Westerners Asian directors choose, yet they are payed large sums of money to fly over and act with a foreign crew. I can see director Park just looking at some headshots of Steve Taschler (Capt. Smith), and maye a few clips and giving him the go ahead. Because, in reality, Park probably isnt fluent in English, which would probably put a huge damper on being able to tell an actor's skill. I think the same thing happened earlier on in American cinema before there were so many established Asian actors and actresses. In the 80's and even early 90's, if an Asian actor was needed for a supporting role, his look and his fluency probably mattered more than anything else, not his acting skills haha. W/e, hopefully the trend begins to die down as ties between Eastern and Western cinema continue to strengthen.

ReplyDeleteOh, Hisaishi has an extensive history in film, with Miyazaki and with others. Specifically with Takeshi Kitano he's produced some his best music. If you haven't seen any of his films I'd strongly suggest a movie like "Kikujurio" or "Hana-bi", cult classics among Japanese cinema. Hisaishi does wonders there! And I'm bumping JSA to the top of my list. I adore Park Chan-wook. I'm a little behind in my writings; might knock out a double feature reveiw to get on track. But I'm excited for JSA! Any other suggestions? lol

I know Hisaishi is a hugely prolific composer and has worked on countless non-Miyazaki projects. I just haven't gotten around to checking most of those out myself.

ReplyDeleteIf you're asking about suggestions related to North-South Korean relations like Welcome to Dongmakgol and Joint Security Area, Shiri is a great action flick, despite some of its clichés. I don't know what you have and haven't seen, of course. I'll consider your recommendations. I haven't paid a great deal of attention to most modern Japanese cinema (I love the classics) aside from Hayao Miyazaki and a few mindless J-horror flicks. This is because I prefer South Korean, Hong Kong, and even Thai cinema, but I'm always looking to expand my horizons in new ways.

Oh, and Park Chan-wook is, indeed, a god.